Stories

Shared Health Indigenous Health is dedicated to improving the health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples through the advancement of priority initiatives, and expanded awareness, access, and knowledge of Indigenous health Services across Manitoba.

As part of our work to build awareness, we are proud to share these stories featuring Indigenous leaders, health-care workers and community members working towards improving equity, diversity and access across Manitoba’s health-care landscape.

- Ann Thomas

- Joyce Noonen

- Martha Baker

- Churchill’s Warrior Caregiver Program

- Annabelle Anderson

- Dagan Amyot

- Charlene Lafreniere

- Faye Tardiff & Raine Seivewright

- Doretta Harris

- Adam Sanderson

- Donna Head

- Bev Swan & Jason Swan

- Beatrice Campbell

Ann Thomas

The legacy of Manitoba nursing can be found in the story of Ann Thomas Callahan RN, BA, MA, Wapiskisiw Piyésís Iskwéw (White Birdwoman).

As the first Indigenous nurse to work at Winnipeg’s Health Sciences Centre, Ann spent her career making important contributions and critical improvements to Manitoba’s health system, including work that helped to train a new generation of nurses.

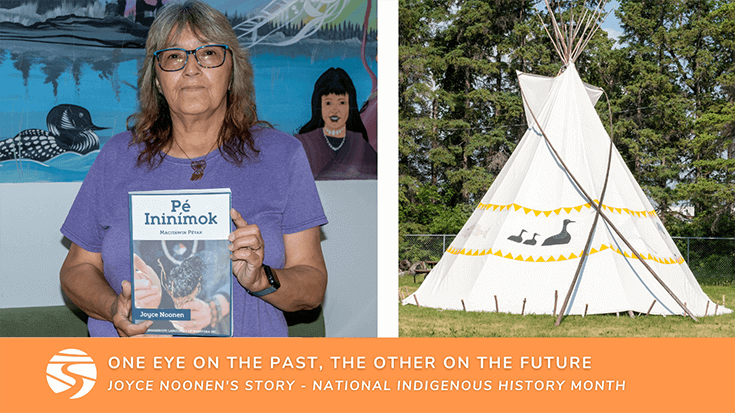

Joyce Noonen

Joyce Noonen has a keen understanding of the past and a sharp eye on the future.

Born in the remote northern community of God’s Lake Narrows, Noonen spent the early years of her life immersed in the traditional Cree language and customs – knowledge that she now spends her time preserving and passing along to younger generations as part of her work at the Selkirk Mental Health Centre (SMHC).

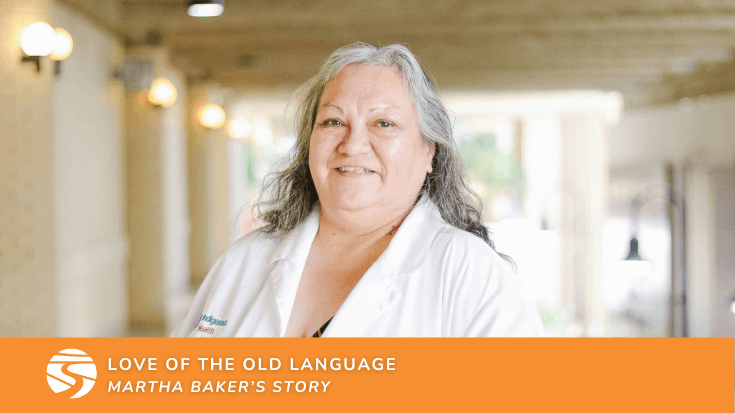

Martha Baker

Martha Baker is of Cree descent. She traces her journey to Winnipeg back from where she was born in the small northern community of South Indian Lake, Manitoba. This is where she learned to speak Cree – a gift she now uses to support Indigenous patients seeking health services at Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg.

“I actually left northern Manitoba to pursue studies at university heading towards a career in education,” said Martha. “But when I was recruited into health care, I saw the opportunity to be a voice for Indigenous people, especially those who come from northern communities. And I remember thinking to myself, ‘now this is interesting’.”

The community of Churchill, Manitoba has recently emerged from winter, a season marked with intense cold and prolonged darkness when the sun – at times – is only visible for six hours a day. Local residents, human and animal alike, have spent the past several months surviving – and thriving – in this remote northern town along the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay.

In this community of less than 1,000 people, where access in and out requires a two-hour flight or a 48-hour train ride, isolation can be a very real phenomenon. Amid this rugged wilderness, survival and connection rely upon a combination of innovation and technology as well as traditional life skills developed over the centuries that Churchill has served as a meeting place.

Annabelle Anderson

I was born and raised in Churchill, Manitoba – but my people are not from here. My mother is Sayisi Dene from Duck Lake, Manitoba. She – and our people – were relocated to Churchill in the 1950s by the Canadian government. My mother was placed in a residential school, which nearly destroyed our culture and way of life. Today many of my people live in Tadoule Lake because Churchill does not always feel like a welcoming place to us. These memories and experiences – and those of my mother, my people – have molded me into someone who can never sit still. I am a doer. I feel the constant need to help anyone and everyone which is what lead me to working in health care.

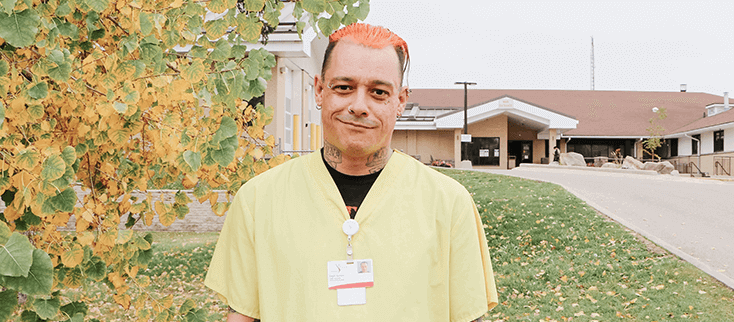

Dagan Amyot

It’s shift change at Portage District General Hospital (PDGH), and murmurings of “morning” are heard throughout the halls as staff and patients start their days. In the rehabilitation unit, a cheerful “good morning!” rings from someone with a demeanour as bright as their scrubs.

For Dagan Aymont, a health care aide at PDGH, that bright tone is as intentional as his wardrobe.

“I try to start every day with positivity. I notice many people in healthcare say ‘morning,’ but I make sure to say ‘good morning’ with a bright tone,” said Dagan Aymont, a health care aide at PDGH.

Charlene Lafreniere

My connection to family and ceremony is a huge part of who I am. Knowing my identity and being really proud of it is something I have very intentionally passed down to my daughter. I want her to be very connected to where she comes from, whether through family connections, stories, traditions and ceremony or by developing an understanding of the land and all that it gives us.

Wherever I can create that space for culture and connection to spirit for her, I do. She loves ceremony, and she loves church-a reconciliation I am proud of. We talk about the medicine, we have a hand drum we share, and we sing together, a tradition that we have made all our own with the songs that we know by heart outside of ceremony.

One of the many steps we can take toward reconciliation is to access education on the historical impacts of colonization on Canada’s Indigenous peoples.

Within the Winnipeg Health Region, Indigenous Health Education and Training Coordinators, Faye Tardiff and Raine Seivewright, deliver cultural competency training for health-care professionals, part of the organization’s efforts to fulfill number 23 of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission 94 Calls to Action.

Doretta Harris is Regional Lead of Indigenous Health in Southern Health-Santé Sud and has spent the past 15 years of her career building relationships and health programs intended to improve health care experiences, and ultimately, health outcomes for Indigenous people and communities.

“My life experiences as a First Nations woman have helped to shape who I am, clarified my priorities, and made me stronger and more resilient; but these experiences have also made me more compassionate toward others who face challenges and health disparities,” said Harris.

-Eastern Regional Health Authority covers 61,000 square kilometers and supports a population of 137,442 people, including 17 First Nations communities. With 27 per cent of the region’s population identifying as Indigenous, the IERHA Indigenous Health department plays an integral role in the delivery of local health services, under the leadership of new Director Adam Sanderson, whose roots run deep in the region.

Donna Head’s face lights up as she talks about the arrival of a trailer full of supplies for the Northern Health Region’s Land Based programs.

“I like where we are going,” said Head, Indigenous Health Coordinator for the Northern Health Region. “We are incorporating more traditional and cultural Indigenous practices into the health care setting. It’s exciting to see the steps that our department, and other Indigenous Health departments are taking to move forward in a good way.”

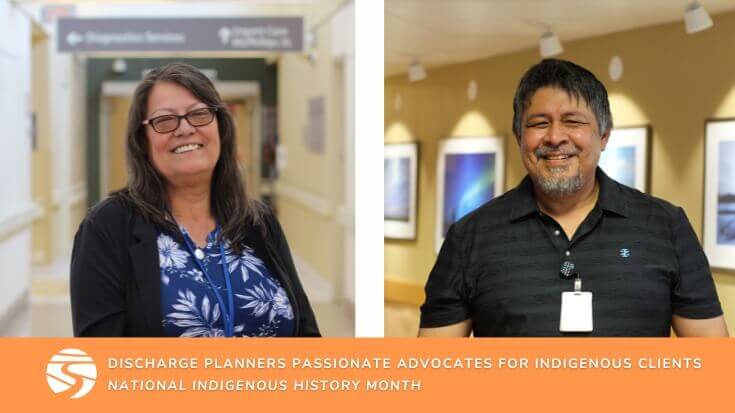

Bev Swan and Jason Swan aren’t just cousins, they are also Winnipeg’s only Regional Discharge Planning Coordinators, a role unique to the Indigenous Health program.

“We support patients with only the most complex cases, those that have discharge challenges and barriers to plan for,” said Bev. “Challenges may include homelessness, jurisdictional barriers, going home for end-of-life care in a First Nations community, or anything that may challenge a discharge from hospital.”

Beatrice Campbell is an advocate, a navigator-for-navigators, a social worker, and a resource for education and learnings in her role as Regional Patient Advocate for Indigenous Health in Winnipeg. With 21 years of experience working in the Winnipeg Health Region in both acute and community environments and more than 30 years working with Indigenous individuals, she uses all of these skills to support patients and their families as they seek and receive care.

The broad scope of Campbell’s role gives her a unique lens to observe trends that impact Indigenous patients as they move from site to site, program to program, across the region and province and identify opportunities for changes at the individual and systemic levels.